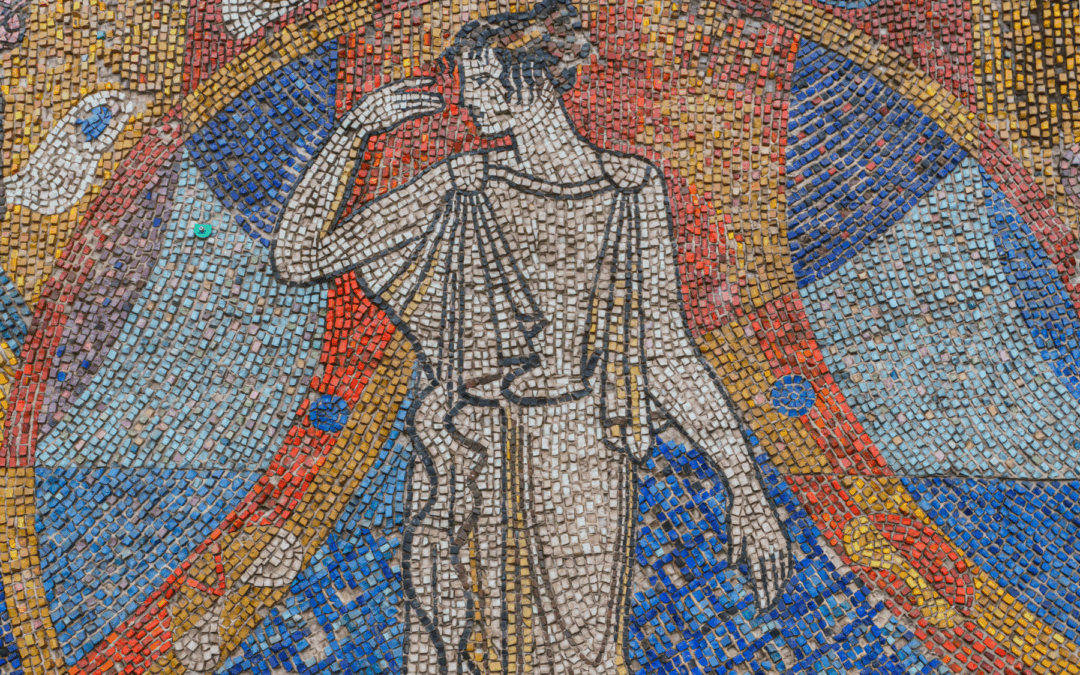

When people think of Soviet art, they often imagine propaganda posters with bold graphics and socialist realism paintings depicting heroic workers and idealized scenes. But some of the most fascinating and complex artistic expression from that era is literally embedded in walls across Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the former Soviet republics—in the form of monumental mosaics.

These weren’t just decorative flourishes added to make buildings look nice. They were deliberate, carefully planned works of art that served multiple purposes: to inspire, to educate, to celebrate, and yes, sometimes to persuade. Understanding what these mosaics depicted and why requires looking beyond the surface beauty of their colorful tiles.

A mosaic in a workers’ club might celebrate labor and industry, showing figures engaged in construction, manufacturing, or agricultural work—emphasizing the dignity and importance of the working class. One in a school might depict children learning, playing, and growing, symbolizing hope for the future and the importance of education in building a better society. Metro station mosaics often showcased regional culture, featuring local heroes, significant historical events, or the distinctive characteristics of the area they represented.

The imagery wasn’t random. These mosaics conveyed stories and captured emotions in ways that resonated with the people who saw them daily. A mosaic depicting the cosmos and space exploration spoke to Soviet pride in scientific achievement. One showing traditional folk motifs connected modern Soviet citizens to their cultural heritage. Scenes of peace and prosperity communicated ideological messages about what the state was working toward.

What makes them so interesting from a cultural and historical perspective is that they captured the ideology, hopes, and daily life of their time. The bright, bold colors weren’t just aesthetically pleasing—they were meant to be uplifting and energizing. The monumental scale wasn’t just impressive—it was meant to inspire awe and convey the importance of collective achievement over individual concerns. The choice of subjects, the style of representation, even the locations where these mosaics were placed—all of this tells us something about the values and priorities of Soviet society.

But these works also show us something beyond politics and ideology: the incredible skill of the artists who created them. Working with thousands of tiny tiles—often ceramic or glass pieces called tesserae—these craftspeople created works that have lasted decades and in many cases remain vibrant and striking today. The technical challenges were enormous. Planning a composition that would work at massive scale, selecting and arranging tiles to achieve the desired colors and effects, executing the installation often many feet above ground or in difficult conditions—this required not just artistic vision but masterful technique.

Many of these artists worked under constraints that would be unimaginable to contemporary artists. Materials might be limited or of inconsistent quality. The subject matter might be dictated by officials rather than chosen freely. Approval processes could be lengthy and politically fraught. Yet despite these challenges, or perhaps because of them, the artists found ways to infuse their work with creativity, beauty, and sometimes subtle forms of personal expression.

Understanding the social, political, and cultural context behind these mosaics helps us see them not as relics of a bygone era, but as windows into a complex period of history. They document the artistic movements of their time—from the socialist realism that dominated official Soviet art to the more abstract and modernist approaches that emerged in later decades. They reflect changing attitudes toward tradition, modernity, nationalism, and internationalism. They show us how art functioned in a society where it was expected to serve public and political purposes.

These mosaics are fragments of collective memory. For people who grew up seeing them daily, they’re part of the backdrop of childhood and daily life—as familiar and meaningful as any monument or landmark. For younger generations, they’re intriguing artifacts that prompt questions about the past. For all of us, they’re reminders that every era expresses itself through art, and that understanding historical art helps us understand historical people.

That’s what we’re trying to preserve: not just art objects, but memory, context, and meaning. When we document a mosaic, we don’t just record what it looks like—we research when and why it was created, who made it, how it was received, what it meant to its community. We’re building not just an archive of images, but a comprehensive resource for understanding this distinctive art form and its place in 20th-century cultural history.

Because these works deserve to be understood as more than just pretty tiles. They’re testaments to artistic skill, historical documents, cultural artifacts, and yes—they’re also genuinely beautiful examples of an art form with roots stretching back over two thousand years to ancient Mesopotamia. All of these dimensions matter, and all of them are worth preserving for future study, appreciation, and inspiration.