Geometry has always shaped the visual language of Slavic art. Whether found in textiles, carved woodwork, or monumental mosaics, geometric structure forms a quiet backbone behind the imagery. When viewers learn to recognize these underlying patterns, historic mosaics become easier to understand—and much more enjoyable to explore. Geometry doesn’t merely decorate these works; it organizes them, guides the viewer’s eye, and reflects centuries of shared artistic vocabulary.

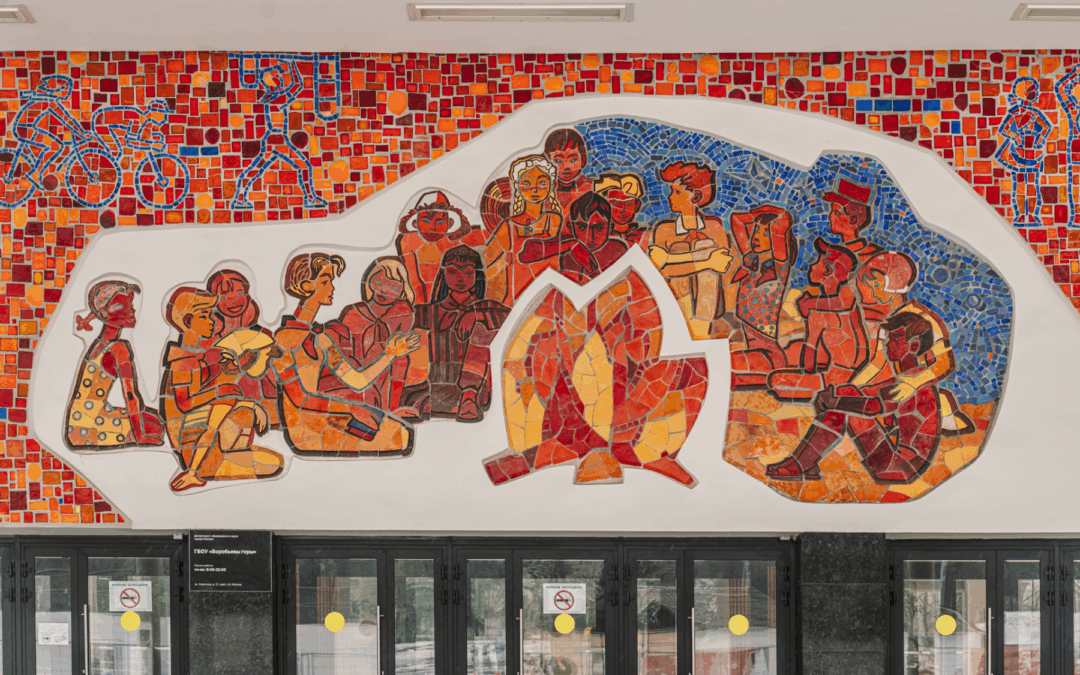

Many pre-Soviet and Soviet-era mosaics relied on geometric composition as a form of visual balance. Squares, triangles, diamonds, and radiating circles appear repeatedly in both central scenes and ornamental borders. These shapes echo older folk crafts, particularly weaving and embroidery, where geometric motifs were essential. Mosaic artists carried these traditions into large-scale architectural works, preserving their structure even as styles modernized.

In many mosaics, geometry begins with the background. Artists often created repeating diamond grids to establish rhythm behind human figures or natural elements. This repetition doesn’t distract; it creates harmony, giving the main subjects a stable stage. The slight irregularity of hand-placed tesserae—tiny mosaic tiles—adds warmth to these patterns, preventing the work from feeling mechanical.

Borders add their own layer of subtle geometry. Many Slavic mosaics feature patterned frames with alternating triangles, stepped zigzags, or interlocking shapes. These borders don’t merely enclose the scene; they echo traditional craft motifs found in ceramics and woven belts. They visually “anchor” the narrative, connecting modern public art to older artistic knowledge.

The use of radial geometry is also common. Sun motifs—representing life, energy, and continuity—appear frequently in Slavic art. Mosaic artists used radiating lines to create movement within otherwise static scenes. When placed behind a figure or emblem, radial patterns help guide the viewer’s focus toward the central message of the artwork.

Another important geometric element is proportion. Many mosaic compositions follow a gentle sense of symmetry, even when depicting dynamic scenes. Artists often balanced a prominent figure on one side with geometric weight—such as a symbolic motif—on the other. This creates equilibrium without strict mirroring, a hallmark of Slavic design that aims for harmony rather than mathematical perfection.

Understanding the geometry embedded in mosaics also reveals insights into craftsmanship. Skilled artists used angled placement of tesserae to “draw” lines of geometry with texture instead of paint. When viewed up close, these angled lines shimmer, reflecting light differently from surrounding areas. It’s a subtle way geometry interacts with physics, giving mosaics a living quality that changes with the sun.

Recognizing geometric clues helps any traveler or art lover connect more deeply with historic mosaics. These patterns are more than decoration—they carry cultural memory. They reference centuries of craftspeople who used shape and structure to express shared identity. When viewers learn to spot this geometry, the art becomes richer, more layered, and more connected to the traditions that shaped it.